Lecture 1: Neoclassical Growth

The aim of this course is to provide you with an understanding of the mechanisms behind modern economic growth. We'll focus mainly on developed or transitional economies. While there are many interesting links between growth and development (and we will discuss these), a full treatment of the latter is beyond the scope of this course.

There will also be a strong focus on computational methods. Though the study of this topic can be quite interesting in its own right, our primary motivation here will be using the theoretical tools we will have developed in conjunction with computational techniques to generate detailed quantitative predictions. These can in turn help us estimate the parameters particular and refine our understanding of how realistic certain classes of models are.

As a practical matter, one needs choose an environment in which to carry out computation. I'm personally OK with any choice you might make, but I would recommend using Python, as it's free, easy to use, and has a lot of support available both from me and online. In particular, there is a good deal of information on using Python for economics from Tom Sargent and John Stachurski at Quantitative Economics.

Conceptual Framework

There will be theoretical, empirical, quantitative, and technical considerations covered for each topic we address. At this highest level we can decompose output, and consequently growth, into contributions from four sources:

- [Physical] Capital ($K$): This is a major driver of economic growth and has been very well studied in the field of economics. I'm going to assume you have some familiarity with the basic models of capital accumulation here.

- Human Capital ($H$): Education, on-the-job learning, health, childhood development, etc. This is, oddly, somewhat more of a niche product. Nonetheless, it's very important and we'll be looking at it.

- Labor ($L$): Here we speak mostly of population growth, but this can also include other factors such as hours worked. This may all wash out in per-capita terms, but there are important considerations here regarding scale effects, which we'll see in .

- Total Factor Productivity ($A$ or $z$): This is basically the leftovers, and it will be our primary focus. It captures basic scientific knowledge, practical knowledge, methods, designs, managerial practices, and the like. We'll be trying to unpack this black box as the course moves along.

This gives us a structured way in which to think about the causes of economic growth. Of course, attributing a particular fraction of growth to capital accumulation only addresses the proximate causes of growth. Ideally, we would also be able to gain understanding of why this capital accumulation occurred in the first place. In this way, there will also be many dynamic linkages between each of these components.

Solow Growth Accounting

The Solow model is a mathematical embodiment of the above decomposition. It assumes a single aggregate production function describing how inputs capital ($K$), labor ($L$), and technology ($A$) are combined to produce final good $Y$ according to

Often it will be useful to express this relationship in per capita terms. We say that a particular production does not feature scale effects if we can express

Neoclassical Growth Model

The canonical model studied in computation macroeconomics is the neoclassical growth model. Of course, there are many other interesting models out there that are better suited to their phenomenon of study, but this one provides a basic understanding of issues that arise when doing dynamic optimization with a continuous state variable, which is in this case capital.

Much of the basic structure of the Solow growth model is inherited here. We'll basically populate the economy with consumers and firms, then impose assumptions that allow us to meaningfully model the economy with an aggregate production function and representative consumers and firms.

Consumers

One of the major simplifying assumptions we'll be making, at least initially, is that of a representative agent. Naturally, with homogeneous agents, this is not a major assumption. When we start introducing heterogeneity amongst agents, for instance between skilled and unskilled labor, this will be more of an issue since different agents can have different responses that do not aggregate linearly. Sometimes you'll see papers that have a single representative household with heterogeneity amongst the agents in the household.

Let's say this agent has the instantaneous utility function $u(c)$ which is then aggregated over time with discount rate $\rho$

This infinite dimensional optimization is not a trivial one. I'm going to skip directly to the recursive formulation. I'll also take this opportunity to provide a little primer on working in continuous time, as opposed to discrete time. Let the current time be $t$ and the next "instant" in time be $t+\Delta$, where $\Delta$ is presumed to be small. Let the present value of having asset level $a$ at time $t$ be given by $V(a,t)$, then we have

Producers

The final good is produced by a continuum of competitive firms. Because we will assume constant returns to scale, it is just as well to consider the case of a single firm that takes prices as given. We will ignore growth in $A$ for now. Because the population is fixed at $1$, aggregate and per capita variables will coincide, so we can just use lower case letters. As before, let the production function be $y = f(k,\ell)$.

The producer faces the following static optimization problem in which they rent capital from consumers and hire them as laborers in order to produce

Optimization

We can derive an analogous expression for the first-order condition in discrete time

Equilibrium

Aggregate consistency requires that consumer assets be equal to the value of capital and that the labor market clears

Steady State

Let us indicate steady state values with a superscript $\ast$. In steady state, the value of $k$ is not changing, meaning $i^{\ast} = \delta k^{\ast}$. Combining this with the envelope condition in and the first order condition in , we find that the interest rate is

Transition Dynamics

This is where we really start having some fun. It turns out we can define a two variable dynamical system (i.e., a system of differential equations) to describe the solution outside of steady state. Define a new variable

The only remaining problem to solve is the initial condition. We have two state variables $(k,c)$ and two differential equations describing their evolution. We are given an initial value for the stock of capital $k(0)$, we just need to know $c(0)$, which is chosen optimally by the consumer.

So if we derived a solution for this complex optimization problem, why don't we know $c(0)$ yet? It turns out there is a third and final condition (in addition to the first order condition and envelope condition) to ensure optimality, the dreaded transversality condition. This basically states that things shouldn't be blowing up in the limit, be they the capital stock of the marginal utility of consumption.

It turns out that this system is highly unstable around the optimal path $c(k)$, which is called the saddle path. Even a slight divergence will send the capital stock either off to infinity or to zero. If we use the saddle path exactly, then we'll proceed in an orderly manner to $(k^{\ast},c^{\ast})$ in the limit and stay there forever. This means that satisfying the transversality condition is just a matter of riding the saddle path the steady state, but it also presents substantial numerical difficulties.

Transition Paths

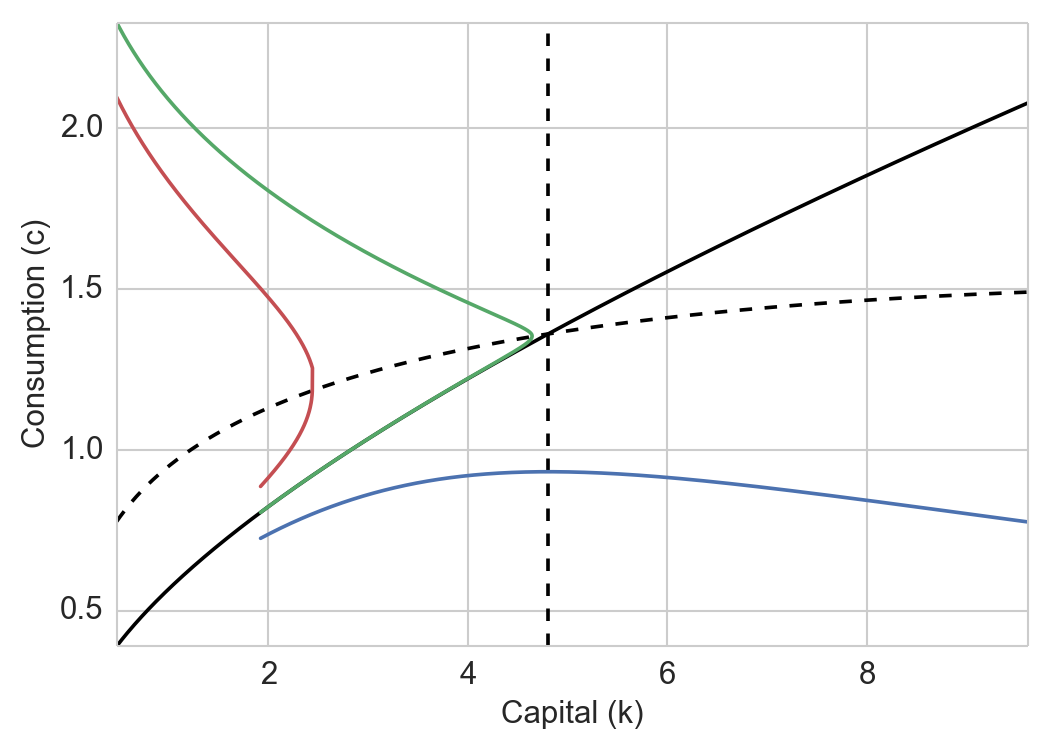

Depicted in is the state space over $(k,c)$. In solid black is the saddle path optimum function $c(k)$. The dotted lines delineate the various regions in terms of direction. To the left of the vertical dotted line (which is at $k^{\ast}$), consumption is increasing, and vice versa. Above the other dotted line, capital is decreasing, and vice versa. These can be computed from the laws of motion for each.

The lines in reg, green, and blue depict various candidate values for $c(0)$. The red line is above the saddle path and skews left into an infeasible region. The blue line is below the saddle path and falls towards zero consumption. The green path is exactly the saddle path choice. Notice that even here, tiny numerical errors prevent us from truly reaching the steady state. This isn't a huge problem as the computed value of $c(0)$ is nonetheless quite accurate, and we can re-update along the path.

Computation

There are two ways to do this: the easy way and the hard way. We can do a brute force discrete time approximation, or we can be a bit clever and get the same results with much less work. First the brute force method. We've already seen that the equilibrium is efficient, so let's just cut straight to solving the social planner's problem. For a given small time step $\Delta$ we have

Now on the the quicker method. The issue with choosing $c(0)$ to hit the steady state (the so called shooting method), as we saw in , is that even double precision floating point precision is not up to the task. There is one way around this: we can reverse time. Systems that are unstable in forward time are often stable in backwards time. By doing this and starting at a point perturbed infinitesimally from the steady state, and using negated laws of motion, we will actually trace out the saddle path.

Technological Growth

With the above framework, we can model and better understand economies undergoing periods of rapid transition, such as those seen in post-war South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and others. Interestingly, undertakes a detailed analysis of this dynamic using the growth decomposition tools we've been looking at. He finds that in those countries, contrary to popular wisdom, the majority of output growth can be attributed not to overall productivity growth (TFP), but to capital accumulation.

Indeed, sustained, long-term (and likely more modest) technological growth is another matter, but will be closely related to the neoclassical growth mechanism. We'll focus for now on the case of exogenous growth TFP. We'll spend much of the course studying the endogenous evolution of TFP, but this is fine for now.

Suppose that the value of $A$ grows at a constant rate $g$ over time, while $L$ grows at rate $n$. That is, $\dot{A}/A = g$. Recall that the steady state capital level satisfied $f^{\prime}(k^{\ast}) = \delta + \rho$. Because the marginal productivity of capital is decreasing (i.e., $f$ is concave), the steady increase in $A$ must be offset by a concomitant increase in $k^{\ast}$. So $k^{\ast}$ will be growing without bound over time.

Consider the CES production function that we defined in . Let's say we're looking a balanced growth path equilibrium in which the interest rate $r$ is stable, as is the fraction of output spent on capital investment, that is $rK/Y$. Jointly, these imply that $K$ and $Y$ must grow at the same rate. However, looking back to , we can see that $g_Y = g + g_K$ (assuming $g_K = g_w$), a contradiction when $g \gt 0$.

What to do then? Let's try introducing factor specific technological terms $A_K$ and $A_L$ like so

- Technological change is purely labor augmenting, that is $g_{A_K} = 0$.

- Utility is Cobb-Douglas, that is $\sigma = 1$. In this case $A = A_K^{\alpha}A_L^{1-\alpha}$.

The last assertion in the second clause is left as an exercise to the reader. This is an important result in the study of directed technical change, which we will look at later in the course. In the meantime, interested readers can consult for a more detailed treatment.

Exogenous Growth Model

Let's consider only the simplest setting, in which the per-period utility function and production function are given by

Outside of steady state, we can still make some headway. As before, define the function $m(t) = \tilde{V}_{\tilde{k}}(\tilde{k}(t))$, which is the value of the derivative along the optimum path. Consider the case of a known productivity path. Then we have